|

In 1675 Francis was 17 and had been pretty much forcibly removed from the company of a girl he found to be wonderful. His father had to move the family from Sebascodegan to Truro on Cape Cod to try to avoid the Indian Wars. The fact that the girl was of the Abenaki tribe had not been an issue all through their childhood together. All of Francis Sr. and Elizabeth’s children had played with the native children for as long as they could remember. Algonquin and English were co-first languages for them.

That Francis and Willow were to be on opposite sides in a conflict not of their making was not going down well with the young lovers. Francis Sr. sympathized with his son but the family must move for their own safety. For over a year Francis pined for his Abenaki maiden. There was no question of her joining him. The English would not stand for it. Already the sentiment that the only good Indian was a dead Indian had emerged among many English settlers. There was however a long tradition among the Abenaki of adopting young men of whatever background into their tribes. In the September of 1676, Francis won his parent’s permission to join the Abernaki.

It might seem a strange choice but the Smalls and the Abenaki of Sebascodegan had been friends and neighbors for two generations. Francis Sr. knew quite well that the Abenaki usually simply disappeared when threatened. He was confident that even if Francis could locate his former neighbors, they would withdraw to Canada rather than fight.

Francis returned to Sebascodegan in one of the family’s fleet of fishing boats. The place was deserted when he arrived. He traveled eastward along the coast through Penobscot Bay and the wild land to the east of that. As he went along he stopped to question both English and natives about the fate of the Sebascodegan clan. Finally somewhere east of Mount Desert he ran out of English and began to find French traders and fishermen, with whom he conversed in Algonquin. No one had any news of the people for whom he was hunting.

Francis eventually reached the St. Croix and pulled in at an encampment on the south side of the river where there was a Jesuit priest and his flock of native converts. There he heard rumors of some Abenaki from Casco Bay who had passed through in the spring and headed north into the Gaspe Peninsular. By now it was November; no time of year to try sailing around Arcadia to the mouth of the St. Lawrence. Francis thought he would tie up his boat to strike out overland but the people explained to him that it was a 300 mile trip to the St. Lawrence and he could no more walk it in winter than he could sail.

One of the Micmac men in the encampment, named Owl Eyes, wanted to go to the Gaspe anyway so he convinced Francis to wait until the weather broke in the spring. Then he would join Francis to either walk or sail as conditions warranted. So Francis stayed with the Micmac people until the middle of May in 1677.

Francis and Owl Eyes had to decide between a 300 mile walk and a 900 mile sail. The walk might take less time, perhaps less than a month, but the sail was a lot more convenient. Supplies could be carried and the boat provided shelter. Also they could fish along the way. Owl Eyes had no experience with boats but he knew enough about long walks to readily agree to the sea voyage.

They launched their boat, loaded it with everything they thought might come in handy and sailed away. Religion had never been at the center of Francis’s life but spending the winter with the Jesuit trying to convert him to Catholicism put him off it altogether. He was never so glad to be leaving a place.

Working from an English chart, with nothing but a compass and a speed log for navigation, Francis sailed across the mouth of the Bay of Fundy, along the Arcadia coast, through the Cabot Strait and across the Gulf of St. Lawrence into the mouth of the great river. It took 37 days.

There on the shore of the Gaspe Peninsular he did find an Abenaki encampment including people recently arrived from the south but they were not the clan he was seeking. He learned that the Sebascodegan clan had not come east, as most of the Abenaki fleeing New England did to avoid the possible contact with the Iroquois, but northwest by the shortest route heading for an encampment just west of Quebec City on the south side of the river.

Owl Eyes said he had nothing more important to do so he would accompany Francis upriver to Quebec City. In fact he was caught up in Francis’s quest and stayed with him as they found the tributary feeding the St Lawrence from the south, a bit west of Quebec City. There was the encampment of a hundred displaced Abenakis at a place the French called St. Romauld. Here Francis learned that Willow’s family had fallen behind due to an injury to her father and had probably wintered near Lac Megantic, just across the border from Maine into Canada. They would likely be along later.

“Likely be along later”, was not good enough for Francis. He was all for following the trail back from St. Romauld to Lac Megantic to search for Willow. Owl Eyes again said he had nothing better to do and more importantly he had followed that trail before. Francis gave his boat to the Abenaki with the understanding that he would pay something for it if he made it back and he and Owl Eyes started almost due south for the Lac.

The journey was about a hundred miles as the crow flies. They arrived at the Lac Megantic encampment in mid-summer, 1677. There they found people whom Francis knew from Sebascodegan. From them he learned that Willow’s father had died of an infected wound. Willow’s mother placed herself and the children under the protection of a distant relative from the western Abenaki or Sokoki tribe.

Willow’s new stepfather was a warrior who was headed to a place near Springfield, MA to fight the English. He was taking his new family to a safe place in the hills east of the Connecticut River where he would leave them with others of his clan.

Francis wanted to follow but Owl Eyes pointed out the he was English and apt to have trouble among the Sokoki, even if he could avoid the Iroquois. Francis’s solution was to become a Frenchman. He had gained one important skill in his stay with the Jesuit; he could speak French.

Owl Eyes said he had nothing more important to do so they set out together along the trail to the Connecticut River valley, Francis as a Frenchman and Owl Eyes as an Abenaki. The twisting path followed the high ground that marks the border between Canada and Maine, and Canada and New Hampshire. This tortuous route avoided the swampy terrain that lay in the lower land on both sides of the border. At the headwaters of the Connecticut River the trail left the high ground and followed the river valley southwest.

Just south of the Massachusetts border, in the hills to the east of the Connecticut was the village where Willow and her family had gone. It was about a 300 mile walk and took them until fall of 1677. Owl Eyes convinced Francis to be circumspect in his greeting the family, who knew him to be English. They arrived and sought out the leader of the village and asked if they might remain and refresh themselves before continuing south.

The village leader agreed and introduced them around as a Frenchman and his companion, a maritime Abenaki. Willow had last seen Francis in the spring of 1775 at age 17. Now he was nearly 20 and quite thin. She gave no sign of recognizing him. He did recognize her and noticed that she was no longer among the children but among the married women of the village. Owl Eyes made some discrete enquires and found that she had taken a warrior husband less than a month earlier.

Owl Eyes counseled Francis that the kindest thing for Willow’s sake would be to never let her know he had followed her and Francis agreed. They remained in the village only as long as etiquette required.

On their departure they presented the village leader a gift of a Shawnee tobacco pipe that Owl Eyes had traded for previously. He summoned one of the women to bring a hatchet to the travelers. Willow walked up and looking Francis in the eyes made a speech presenting the gift to him. She included in closing that as a child she knew a “French” boy at Sebascodegan.

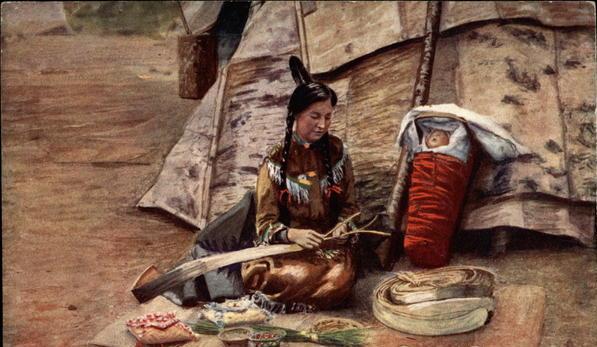

Abenaki Woman Tending Child

Owl Eyes said that since he had nothing more important to do, he would accompany Francis down the Connecticut to the sea. They rafted down through Massachusetts to the confluence of the Chicopee where they ran afoul of a war party and had to join them in attacking a settlement village on the river. An Englishman was taken prisoner and in the night, Francis helped him escape before he and Owl Eyes themselves slipped away.

Before winter set in, Francis and Owl Eyes made it to Lyme where Francis booked passage for himself and Owl Eyes to Portsmouth, RI with a coastal trader. The idea was to walk from Portsmouth to Truro so Francis would at last be home.

As it turned out, they were delayed at Portsmouth. The folks of Rhode Island were famous for their tolerance but it did not extend to Owl Eyes. He was not a “tame” Indian, one in the employ of a white settler, but a “wild” one, traveling with an Englishman hardly civilized himself.

Francis knew of the Hicks family in Portsmouth from his father’s business dealings with Samuel Hicks so he went to Samuel to try to get him to vouch for Owl Eyes. Samuel knew and respected Francis Sr. so he agreed to take Francis and owl Eyes into his household for as long as they would stay in Portsmouth. In fact, Samuel offered them employment for the winter in his shipyard. Francis was about out of money and agreed, sending word on to Truro that he was alive and well and would be home in the coming summer.

In the spring, Owl Eyes said he would like to go back to Canada. Francis said he didn’t have anything more important to do. He convinced Samuel Hicks to let him take a boat with the promise that either he or his father would pay for it. Samuel and Owl Eyes sailed from Rhode Island to Truro where Owl Eyes was introduced to the family and the story of his and Francis’s adventure was told. Then they sailed to Quebec where Francis recovered his father’s boat.

Francis gave that boat to Owl Eyes, who had learned to sail and navigate in his time with Francis. Owl Eyes said he would become a coastal trader with his new vessel. They said good-bye and Francis sailed back to Truro, arriving on the first of November in 1678.

After a stay at home in the winter of 1678-1679, Francis returned to Portsmouth, RI to work for Samuel Hicks again. He settled into a routine of working in the Hicks shipyard fall and winter and fishing out of Truro with his uncle Edmond spring and summer.

In the fall of 1680 it occurred to Elizabeth Hicks that there was nothing more attractive than a handsome, well mannered young man with a mysterious past who was gone about half the time. Elizabeth was the 21 year old daughter of Samuel Hicks. Francis had never shared with the Hicks family the reason for his odyssey through the frontier. It led to considerable speculation that he and Owl Eyes were spies.

Elizabeth fell hopelessly in love with Francis. She sought out his company and sent out signals and Francis was always friendly to her but seemed to lack romantic interest. She persisted and finally in 1683 was driven to a unilateral statement of her love for Francis and asked if there were any hope for her.

Francis told her about his childhood among the Sebascodegan Indians and love affair with Willow. Elizabeth said she did not expect to be Francis’s first love, just his last. They were engaged, to the delight of the Hicks’s and the Smalls, and in 1685 were married.

Initially they settled in Kittery among Francis’s southern Maine relatives. Like his father Francis traded and fished, living in both Kittery and Truro as business dictated. Francis and Elizabeth had five children:

Francis Small 1686, Kittery, ME

Samuel Small 1690, Truro, Barnstable, MA

Daniel Small 1691, Kittery, ME

Joseph Small 1696, Truro, Barnstable, MA

Sarah Small 1700, Kittery, ME

In 1710 Francis died of pneumonia. Elizabeth died in 1712 of a wasting sickness.

|