|

In April 1641 Thomas Jones was helping a neighbor clear some land of timber. He was trimming limbs from a fallen tree when the limb he cut released a previously unnoticed sapling which was bent under the limb. The sapling snapped straight when released and struck Thomas on the left forearm breaking both major bones.

Thomas had his friend close the fingers of his useless hand tightly around a branch. Then Thomas strained backward to straighten the unnatural angle in the middle of his forearm. In so doing he probably set the bones without any more knowledge of anatomy than that his arm should not have an angle between his elbow and wrist. It hurt to hold his arm level so the friend rigged a sling from a sleeve he cut from Thomas’ shirt and they hiked out through the woods to Thomas’ home.

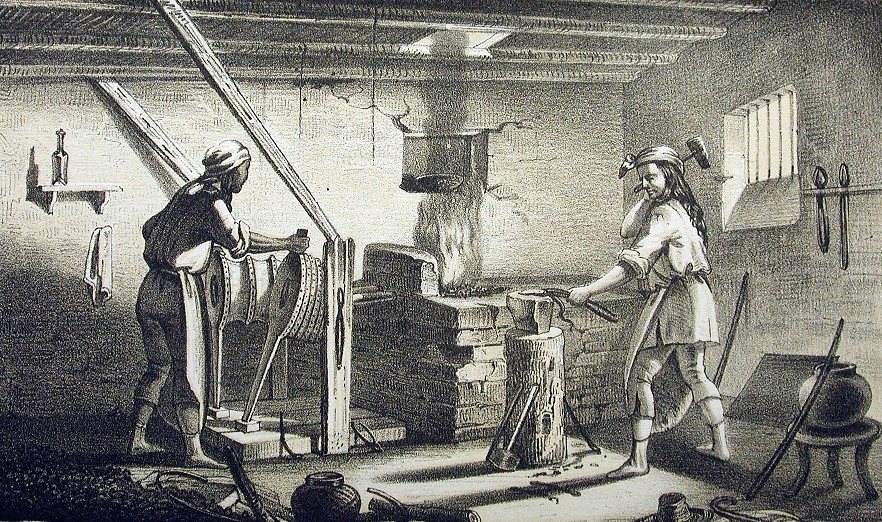

A one armed blacksmith is at a serious disadvantage so while Thomas’ arm healed, he and Mary worked together in the smithy. She would hold a piece in the forge while Thomas worked the bellows. Then she would hold the piece on the anvil while Thomas, with his good right arm used the hammer.

After Thomas recovered and returned to work, Mary continued tinkering in the smithy and developed a double tempering technique that made extra tough and sharp axes. She marked them with her initials MJ and woodsmen from Connecticut to Maine came to call their axe "Mother Jones", saying the axe would take care of them like a mother. A genuine "Mother Jones" was a prized possession.

Mary’s skill in the smithy was not universally admired in Gloucester. Some women in the village began wondering aloud how a female could do a man’s work and still be a godly woman. The accusations started as insinuations and grew over several months to become a real threat.

Still the gossip about Mary might have come to nothing but in Gloucester, as in all the Massachusetts Bay Colony, all the male church members made decisions about the running of the town. In that arrangement not all male church members were equal in influence. In particular there were two men in Gloucester, who were vying for influence by trying to one-up one another in their piety. One of these, Edmund Dunlap, thought that the gossip provided an opportunity to demonstrate his deep religiosity.

In May 1651, Dunlap accused Mary of witchcraft because of her unique skill in making axes. No godly woman could turn out such a product when all others could not, besides, blacksmithing in not womanly work. Dunlap, as prosecutor, convened the grand jury to hear the charges. The grand jury was technically a civil, not an ecclesiastical body. However in Gloucester it was made up of 15 male church members.

On June 30 1651 Mary, eight months pregnant, was brought before the grand jury to defend herself. Witnesses were called to testify to Mary’s hard work and good nature. None could be found to say they had seen her exhibit any witch-like behavior like flying or laying on of curses. That left only the making of the axes to be accounted for. Mary offered to show the jury exactly how it was done, so the next day the jury convened at the blacksmith shop.

“Here are two axe heads made from wrought iron”, Mary said. “Neither has been tempered nor honed. Which of you gentlemen would like to choose between them for my test?”

A man stepped forward and picked up both axe heads and hefted them. Choosing one he passed it to Mary. She slid a handle through the axe head.

“Now I need a man to swing this axe for the first part of the test.”

Another juror raised he hand and Mary handed him the axe. Then stepped outside and picked up a stone from the border of her flower garden and placed it on the anvil in the smithy.

“Now sir, please strike the stone as though to cleave it in two.”

The juror took a healthy swing and in fact did break the stone into pieces. Mary took the axe from him and showed it to the jurors. The edge was peened over where it hit the stone to the extent that the iron in the bent area has several large cracks in it. Mary slid the head off the handle and the jurors passed it among themselves remarking on the damage that had been done. Mary took the axe head with tongs and placed in in the forge which Tomas had been raising to a white heat with the bellows.

After a bit of heating Mary took the piece and hammered out the damage, reshaping the blade. Then she replaced it in the forge and brought it to a yellowish red color. Next she plunged it into the tub of water that was in the smithy and swung it swiftly through the water back and forth, raising a cloud of steam. When the axe had cooled to the extent that no more steam was produced, she placed it back in the forge.

When the axe head glowed a dull red it was again dipped in the tub of water but this time held still. Again steam was produced and when it subsided Mary dropped the axe head to the bottom of the tub. When it was cool enough to handle she slipped the handle back through the hole in the head and offered it to another juror while she selected another stone.

Again the axe was swung against the stone and this time broke it cleanly in two parts. The axe head had some minor damage, a slight flattening in the area where it met the stone.

“You see gentlemen that I invoked no spells or did anything that any one of you might not have done yet the axe has been greatly improved.”

What Mary did not say was that it was very unlikely that anyone could by chance hit exactly the right color of the metal in the two heating processes and one might overlook the importance of rapid cooling in the first heating and slower cooling in the second heating. Also she failed to mention her judicious selection of stones.

Mary in the Smithy

The jury failed to return an either a presentment of fault or a criminal indictment in her case.

In all Thomas and Mary had 10 children:

Susanna 1638, Gloucester, MA

Thomas Jones 3/25/1640, Gloucester, MA

Mary 1642, Gloucester, MA

North 2/22/1645, Gloucester, MA

Nathaniel 2/22/1645, Gloucester, MA

Ruth 2/22/1645, Gloucester, MA

Samuel 8/31/1647, Gloucester, MA

Ephraim 4/1/1649, Gloucester, MA

Benjamin 7/31/1651, Gloucester, MA

Remember 8/1/1653, Gloucester, MA

Mary continued to produce "Mother Joneses", even shipping a few back to England, which made her America's earliest exporter of manufactured goods as opposed to raw materials and native trinkets.

In 1660 there was a bit of an upset in Thomas and Mary’s family. In March of that year a ship sailed into Gloucester harbor, flying no flag, and lowered a small boat over the side. Four people got into the boat and it was rowed to the wharf on the waterfront. Two men were rowing, another man sat in the stern and the fourth huddled in the bow of the boat. At the dock the man in the stern pulled out a pistol and forced the person in the bow to climb the ladder up to the wharf. Then the boat was rowed to the ship and hoisted aboard. The ship turned and sailed off to the East.

Susanna Jones, age 22, happened to witness the whole affair and hurried to the wharf to see what was what. A young woman was sitting on the wharf weeping. She was dressed in rough trousers and a heavy coat such as the deep sea fishermen of Gloucester wore. Susanna put an arm around her shoulder and helped her to her feet. Only then did she notice that the woman was obviously pregnant.

It was also immediately evident that she spoke no English. Not knowing what to do Susanna took her back to her mother Mary. Through signs and actions Mary conveyed that she was not to be harmed and she was given a place by the fire and served a dish of warm broth.

Several people saw the ship come and go and word started to spread through the village that it was a Portuguese fishing vessel. The Portuguese had claimed the Labrador and Newfoundland territory in 1502 as part of the Portuguese Empire. It was known in England that Portuguese fishing vessels were still working the Newfoundland fishing grounds.

With the idea that the mystery woman was Portuguese the search for a speaker of the language began. No one in the village was found so Susanna’s brother Thomas, age 20, was dispatched to Boston to locate someone who spoke the language and would be willing to travel to Gloucester. It was about a half day sail each way.

Young Thomas Jones had gone into the fishing trade out of Gloucester as a teenager. He now had a shallop of his own and sailed it into the harbor at Boston. Suspecting that the waterfront was a good place to look for foreigners, he entered the first tavern he found.

“A half of bitter if you please sir.” he said to the barkeep.

“Aye”, answered the man.

“I wonder if you could help me” Tom said. “I have been sent from Gloucester to find someone who speaks Portuguese.”

“Whatever for?” the barman asked.

So Tom told the story of the stranger apparently marooned on Gloucester wharf by the crew of a ship that may have been a Portuguese fishing vessel.

“Well I never heard of such a thing. I would be very careful she not be diseased.”

“She is staying at my parent’s house and seems to be in good enough health. She is quite large with child and eats like a horse. Her skin is the color of milked tea, eyes are darkest brown, her hair is lighter brown with traces of honey color and her face is beautiful.”

“Whoa young feller. You have been paying close attention haven’t you?”

“Well, perhaps I have. But right now the problem is no one can talk to her, or she to us.”

The barman picked up a bung starter and pounded on the bar.

“Any of you folks speak Portugee?” he bellowed to the patrons.

There were a number of negative replies and shakes of the head. After a few seconds delay one young man came forward.

“I know of a man who came from Brazil. He says Portuguese is his native language.”

“Thank you sir”, said Tom. “Where might I find this man?”

“He is a beached sailor employed at the cordage works down the street. I can show you.”

“I would appreciate meeting him. Thank you”.

So Tom came to meet Donato Arocha. He was a man in his sixties, bent and thin. His hands showed decades of handling rigging. Tom explained situation with the stranger in his mother’s house and Donato agreed to return with Tom the next day provided he could get back the day after that.

So Tom set sail at daylight the next day and brought Donato to the Jones house at Gloucester. There the stranger, on hearing him speak, embraced the old fellow and burst into tears. They talked back and forth for several minutes. Then Donato relayed her story.

The woman was called Debora Danca. Her mother was a mameluco, her father Portuguese Brazilian. She fell in love with a Portuguese sailor and travelled with him to Portugal where he promptly died in a waterfront brawl. She wanted to get back to Brazil so she agreed to travel with the captain of a ship sailing from Oporto. She expected to return to Pernambuco but found herself on a fishing expedition on the Portuguese Banks off Newfoundland. She made so much trouble for the captain that he threatened to throw her over the side but thought better of it and dropped her off at the nearest port he knew of which was Gloucester.

“What does she want to do now?” asked Mary.

Donato translated. Then Debora clung to Mary and spoke.

“She wants to stay with you Ma’am”, said Donato. “She says she has at last found peace, in your house.”

“Well she is in no shape to take on another voyage at this point. Thomas may we take her in?”

“If you think it best, Mary”, Thomas said.

So Debora joined the Jones household. Young Tom undertook to teach her English. She had her daughter in about a month and named her Mary. Ten months after she arrived she and Tom married.

In September of 1671 Thomas succumbed to a lung infection, possibly arising from his years of exposure to fumes from the forge. In February 1682 Mary, who had been in poor health for some time, passed away.

|